This article guides family caregivers through the executor’s duties and a practical timeline for settling an estate in the U.S. It links these responsibilities to related caregiver topics — powers of attorney, guardianship, advance directives, and long‑term care contracts — and provides clear, actionable checklists to keep legal tasks on track from immediate steps to closing the estate.

First Steps After a Death: Immediate Duties and Securing the Estate

The first hours and days after a loved one passes are overwhelming. Amid the grief, there are immediate and critical tasks that fall to you as the executor or primary caregiver. Acting quickly and methodically during this initial period is essential to protect the estate and honor your duties. This is not the time for complex legal filings, but for securing the scene and gathering the essential tools you will need for the road ahead. Think of this initial 0 to 14 day period as a mission to preserve and protect.

Here is a practical checklist of your immediate responsibilities.

-

Locate the Original Will and Estate Documents (Days 0-2)

Your first priority is to find the original, signed will. A copy is rarely sufficient for court purposes. Check common storage places like a home office desk, a fireproof safe, or a file cabinet. While searching, also look for any trust documents, pre-paid funeral contracts, or a letter of instruction that outlines personal wishes. Finding these documents quickly is crucial because the will officially names you as executor and provides the roadmap for settling the estate. Why it matters legally: Without the original will, the estate may be treated as if there was no will at all, a process called intestacy, which could drastically alter how assets are distributed. A common pitfall is finding an unsigned draft; only a properly signed and witnessed document is legally valid. -

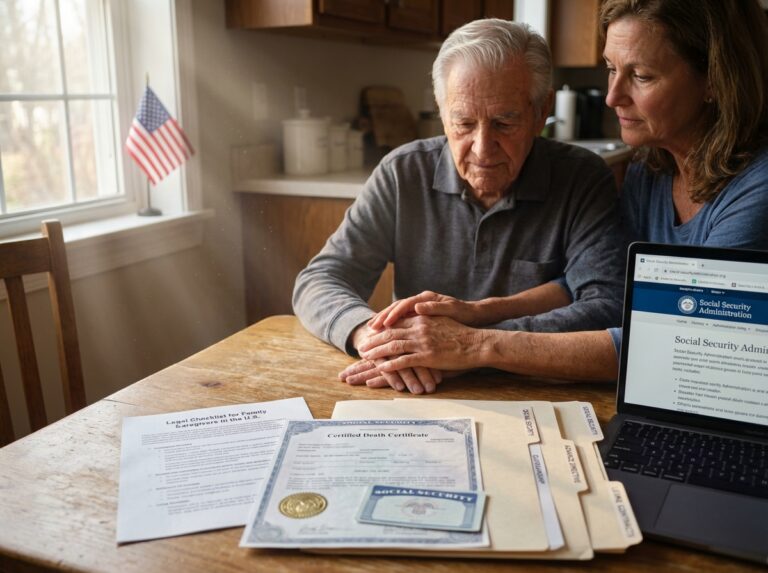

Obtain Multiple Certified Death Certificates (Days 1-5)

The funeral home you are working with can order certified copies of the death certificate on your behalf. It is wise to order more than you think you will need; 10 to 15 copies is a safe starting point. You will need to provide a certified copy to close bank accounts, claim life insurance benefits, notify the Social Security Administration, and transfer vehicle titles. Why it matters legally: This is the official legal proof of death required by all institutions before they will release assets or information. Ordering them all at once is more efficient and cost-effective than requesting them one by one later. -

Secure All Property and Personal Effects (Days 0-3)

This is an urgent and non-negotiable duty. You must protect the decedent’s assets from theft, damage, or unauthorized removal.- The Home: If the decedent lived alone, secure the residence immediately. Change the locks if other people have keys. Notify the local police that the property will be vacant. Forward the mail to your address to prevent mail theft and stay on top of incoming bills.

- Vehicles: Find the keys and titles for all vehicles and move them to a secure location, such as a locked garage.

- Pets: Arrange for the immediate and safe care of any pets, following any instructions left by the owner.

- Digital Accounts: Do not attempt to delete social media or email accounts. Your role is to preserve digital assets, which may have financial or sentimental value. Look for a list of passwords, but do not worry about accessing everything right away.

Why it matters legally: As executor, you have a fiduciary duty to safeguard the estate’s assets. If property is stolen or damaged due to your negligence, you could be held personally liable. A major pitfall is allowing family members to enter the home and take items they believe were promised to them. No assets should be removed until a formal inventory is complete.

-

Notify Key People and Institutions (Days 0-7)

Beyond close family and the funeral home, you must notify the decedent’s employer to stop payroll and inquire about final pay and benefits. Contact the Social Security Administration to stop monthly payments. If payments are issued after the date of death, they will have to be returned. If the decedent was a veteran, contact the Department of Veterans Affairs to inquire about survivor benefits. -

Understand That Power of Attorney Ends at Death (Immediate)

If you were acting as an agent under a power of attorney (POA) for the decedent, that authority ended the moment they died. You cannot use the POA to access bank accounts, pay bills, or manage assets post-death. Your authority as executor only begins once the will is accepted by the probate court and you are formally appointed. Why it matters legally: Using a POA after death is illegal and can result in significant personal liability. -

Preserve All Expense Records (From Day 1)

Start a folder or envelope immediately and label it “Estate Expenses.” Keep every receipt for costs you incur, such as funeral expenses, the fee for death certificates, or the cost of changing the locks. The estate is responsible for reimbursing you for these reasonable costs, but only if you have proof of payment. These records will be essential for the estate’s final accounting.

By focusing on these immediate tasks, you lay a stable groundwork for the more detailed work to come. Your job in these first two weeks is to be a guardian of the estate, ensuring everything is safe and accounted for before you begin the formal legal process of probate.

Gathering Documents and Building the Estate Inventory

After handling the immediate tasks following a loved one’s passing, your role as executor shifts into a detective mode. Your primary mission is to create a comprehensive inventory of the estate. This isn’t just a simple list; it’s a detailed financial snapshot that forms the bedrock for the entire settlement process, from filing with the probate court to paying taxes and distributing assets to the heirs. For family caregivers, who are already masters of multitasking, staying organized here is your superpower. Think of it as creating the ultimate care plan, but this time for the estate’s financial health.

Your first step is to get an Employer Identification Number (EIN) for the estate from the IRS. The estate is a separate legal and taxable entity, much like a person or a business. You cannot use the deceased’s Social Security number or your own. Getting an EIN is free and can be done online in minutes through the IRS website using Form SS-4. You will need this number to open an estate bank account, which is crucial for keeping estate funds separate from your own, and for filing the estate’s tax returns.

With your legal authority established (or in process, as the next chapter covers), you can begin the hunt for documents. You’ll need your Letters Testamentary or Letters of Administration to formally request information from institutions. When you contact them, be prepared to provide a certified death certificate and your executor appointment papers. Keep a log of every call and email; it will be invaluable later.

Here is a detailed checklist to guide your inventory assembly.

- Bank and Brokerage Accounts

Gather recent statements for all checking, savings, money market, and certificate of deposit (CD) accounts. For investment accounts, you’ll need statements showing all holdings like stocks, bonds, and mutual funds. The goal is to determine the exact value of each account on the date of death. - Retirement Plans and Life Insurance

Locate documents for 401(k)s, IRAs, pensions, and annuities. Crucially, identify the named beneficiaries on these accounts. Beneficiary designations often override the will, meaning these assets pass directly to the named person outside of probate. The same applies to life insurance policies. Request claim forms and a statement of the policy’s value at the time of death. - Deeds, Titles, and Mortgages

Find deeds for real estate and titles for vehicles, boats, or RVs. You’ll also need corresponding mortgage statements or loan documents showing any outstanding debt. These documents prove ownership and list any liens against the property. - Business Ownership Records

If the deceased owned a business, find partnership agreements, incorporation documents, or shareholder records. A business valuation by a professional may be necessary. - Safe Deposit Box

If you located a key or records of a safe deposit box, you’ll need to work with the bank to access its contents. This often requires a court order or your official appointment as executor. Inventory everything inside with a bank employee as a witness. - Digital Assets and Passwords

This is a modern challenge. Look for a list of passwords for online accounts, email, social media, and any digital assets like cryptocurrency. Some states have laws granting fiduciaries access, but it can be a complex process. - Government Benefits

Find notices from the Social Security Administration or the Department of Veterans Affairs. You must notify these agencies of the death to stop payments and inquire about any potential survivor benefits for a spouse or dependents. - Outstanding Bills and Contracts

Collect all incoming mail. Gather recent utility bills, credit card statements, medical bills, and personal loan agreements. Also, look for ongoing contracts, such as a long-term care agreement or a lease, which may need to be terminated or settled.

Once you’ve gathered the documents, you must assign a value to each asset. This is the fair market value as of the date of death. For cash accounts, it’s simple. For other assets:

- Real Estate

You must hire a licensed professional appraiser to determine the home’s value. A simple tax assessment or online estimate is not sufficient for the IRS or probate court. - Vehicles

Use resources like Kelley Blue Book or NADAguides to get a valuation based on the car’s condition, mileage, and features. Print the valuation for your records. - Valuable Personal Property

For items like fine art, antiques, or jewelry, you may need another professional appraisal. For general household goods, you can often make a good-faith estimate in a simple list, unless the estate is large enough to require a federal estate tax return.

Finally, create a master spreadsheet or document. List every asset with its date-of-death value and note how you determined that value (e.g., “Bank of America Checking Acct #123 – $5,432.10 per 10/15/2025 statement,” “123 Main Street – $450,000 per appraisal by Jane Doe, 11/01/2025”). On a separate tab, list all known debts and potential creditor claims. This inventory is not just for you; it will be a formal document you file with the probate court and use to prepare any required tax returns. Juggling this with caregiving is tough, so work in small, focused blocks of time. Scan every document you find and save it to a secure cloud folder. This digital backup will be a lifesaver, allowing you to access information from anywhere without digging through a mountain of paper.

Probate Process Step by step timeline and interacting with the court

After gathering all the necessary documents and creating a detailed inventory, your next major task is to navigate the court system through a process called probate. This is where the will is legally validated, and you are formally granted the authority to act as the executor. The path can seem intimidating, but understanding the timeline and key steps can make it much more manageable. The probate process varies significantly by state and the complexity of the estate, but it generally follows a predictable sequence.

First, it’s important to know which type of probate applies, as this dictates the level of court supervision required.

- Small Estate Procedures. Most states offer a simplified process for small estates, often called “summary administration” or “affidavit procedures.” This allows you to transfer property without formal court oversight. The definition of “small” varies widely, from under $50,000 in some states to over $184,500 in others like California. If the estate qualifies, this is the fastest and least expensive route.

- Informal Probate. This is the most common path for estates with a valid, uncontested will and straightforward assets. It involves minimal court supervision. You file the paperwork, and as long as no one objects, you can administer the estate with a good deal of independence.

- Formal Probate. This process is required when a will is contested, the will is unclear, or there are significant disputes among beneficiaries. Formal probate involves more court hearings, stricter oversight, and is generally more time-consuming and expensive.

Once you’ve identified the likely path, you can begin the formal timeline. While a straightforward estate can often be settled in 6 to 18 months, complex or contested estates can easily take one to three years or more.

Step 1. Filing the Petition for Probate (Within the First Month)

Your first official action is to file the original will and a certified copy of the death certificate with the appropriate probate court, usually in the county where the deceased lived. You’ll also file a “Petition for Probate,” a legal document asking the court to validate the will and formally appoint you as the executor. Court filing fees typically range from $200 to $500 and are paid from estate funds. The court will then issue a document called Letters Testamentary (or Letters of Administration if there is no will), which is your legal proof of authority to manage the estate’s assets. Some courts may require you to post a bond, which is an insurance policy that protects the estate from mismanagement. However, many wills include a clause waiving this requirement.

Step 2. Notifying Heirs, Beneficiaries, and Creditors (Months 1-4)

After your appointment, you must formally notify all heirs and beneficiaries named in the will that the estate is in probate. You are also legally required to notify the deceased’s creditors. This is usually done by publishing a notice in a local newspaper for a set period. This publication starts a critical waiting period, typically three to six months, during which creditors can file claims against the estate. You cannot distribute assets to beneficiaries until this period has passed and all valid debts have been addressed.

Step 3. Managing Assets and Filing Taxes (Months 2-12)

During the creditor notice period, you will continue managing the estate’s assets. You’ll use the inventory you previously compiled to file a formal inventory and appraisal with the court, usually within 90 days of your appointment. This is also the time to handle critical tax filings.

- Federal Estate Tax Return (Form 706). This is only required for very large estates. For deaths in 2024, the federal exemption is $13.61 million per individual. If the estate exceeds this threshold, Form 706 is due within nine months of the date of death. You can request a six-month extension by filing Form 4768 before the deadline.

- Estate Income Tax Return (Form 1041). If the estate generates more than $600 in gross income during the year (from things like interest, dividends, or rent), you must file this return.

Step 4. Preparing the Final Accounting and Closing the Estate (Months 12-18+)

Once the creditor claim period has ended, all valid debts and taxes have been paid, you must prepare a final accounting. This is a detailed report for the court and beneficiaries that shows all the estate’s assets, income, expenses, and proposed distributions. After the court approves the final accounting, you can distribute the remaining assets to the beneficiaries. Once all assets are transferred and you’ve filed receipts with the court, you can petition to be formally discharged as executor, which officially closes the estate and ends your responsibilities.

Navigating this process can be complex, and it’s wise to know when to seek help. Consider hiring a probate attorney if the estate is subject to formal probate, if family members are in conflict, or if assets are particularly complex. A CPA is invaluable for preparing estate tax returns. Remember that all professional fees are paid from the estate, not your own pocket. Finally, always check the specific rules for your state and county court. Many courts now offer robust websites with forms, fee schedules, and electronic filing options that can streamline the process.

Managing Taxes, Debts, Distributions, and Estate Closure

Once the court has formally recognized your role as executor, your focus shifts to the financial heart of the estate. This phase is about managing money, paying off debts, and preparing for the final distribution to the people who are waiting. It requires meticulous record-keeping and a clear understanding of who gets paid first. Think of it as balancing the estate’s checkbook before you can close it for good.

The law sets a clear pecking order for paying estate debts. You can’t simply pay bills as they arrive. Distributing assets to beneficiaries before settling all debts can make you personally liable for any shortfalls, so follow this priority list carefully.

- 1. Administration Expenses. These are the costs of settling the estate itself. This includes your executor fees (if you choose to take them), attorney and accountant fees, court filing costs, and appraisal fees. These are paid first because the estate can’t be settled without them.

- 2. Funeral and Burial Costs. Reasonable expenses for the funeral, burial, or cremation are next in line. This also covers costs related to final medical bills from the deceased’s last illness.

- 3. Secured Debts. These are debts tied to specific property, like a mortgage on a house or a loan on a car. Payments must be kept current to prevent foreclosure or repossession.

- 4. Taxes. Federal and state taxes, including the deceased’s final personal income tax, estate income tax, and any potential federal or state estate taxes, have high priority.

- 5. Unsecured Debts. This is the last category and includes credit card bills, personal loans, and utility bills.

As part of the probate process, you will have notified creditors. They have a limited time, typically three to six months, to submit a formal claim. You must evaluate each claim’s validity. If it’s legitimate and documented, you pay it from the estate’s assets according to the priority list. If you believe a claim is invalid, you can formally reject it through the court. The creditor then has a short window to sue the estate to prove their claim. Never ignore a claim; always respond formally.

Navigating the tax landscape is often the most complex part of an executor’s job. It’s also where professional help is most critical.

Federal Estate Tax (Form 706)

This tax applies only to very large estates. For deaths in 2024, an estate tax return is only required if the deceased’s gross estate exceeds $13.61 million. This exemption amount is adjusted for inflation annually and is subject to legislative changes, so you must verify the current threshold for the year of death. If the estate is anywhere near this value, you should immediately hire an experienced estate tax attorney. The return is due nine months after the date of death, though an extension is possible.

Estate Income Tax (Form 1041)

An estate is a separate taxable entity. If the estate generates more than $600 in gross income during the year (from things like interest, dividends, or rent from estate property), you must file a Form 1041, U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts. This is different from the deceased’s final personal income tax return (Form 1040). A Certified Public Accountant (CPA) can prepare this return and help you plan for tax-efficient distributions.

State Estate and Inheritance Taxes

Be aware that several states have their own estate tax or inheritance tax, often with much lower exemption amounts than the federal level. An inheritance tax is paid by the beneficiaries, while an estate tax is paid by the estate. Check your state’s laws, as this can significantly impact the amount beneficiaries receive.

Only after all valid debts, expenses, and taxes have been paid can you distribute the remaining assets.

Transferring Titled Assets

For real estate, you’ll need to prepare and record a new deed to transfer ownership to the beneficiary. For vehicles, you’ll work with the state’s Department of Motor Vehicles to re-title the car. For bank and brokerage accounts, you will present the Letters Testamentary and a death certificate to the financial institution to have the assets transferred to the beneficiaries’ names.

Beneficiary Designations

Assets like life insurance policies, 401(k)s, and IRAs typically have named beneficiaries. These assets pass directly to the designated individuals outside of probate and are not under your control as executor, unless the estate itself was named as the beneficiary.

The final step is to formally close the estate. This involves preparing a final accounting, which is a detailed report of every dollar that came into the estate and every dollar that went out. This report is provided to all beneficiaries and, in most cases, filed with the court for approval.

Here is a simple checklist for the final distribution and closing process:

- Obtain signed receipts from each beneficiary acknowledging they received their inheritance.

- File the final accounting and receipts with the probate court.

- Petition the court for a formal order closing the estate.

- Request an order discharging you from your duties as executor, which releases you from liability.

- Make the final distributions of any remaining funds held in reserve.

- Close the estate’s bank account.

You should retain all estate records, including tax returns, the final accounting, receipts, and court filings, for at least seven years after the estate is closed. This protects you in case of future audits or disputes. For family caregivers managing these tasks remotely, rely on certified mail with return receipts for sending important documents and checks. Use secure cloud storage to share financial updates with beneficiaries and professionals, and schedule dedicated time blocks to focus on estate matters to prevent them from overwhelming your caregiving duties.

Frequently Asked Questions: Common Executor and Caregiver Legal Concerns

What is the difference between an executor and a personal representative?

Think of these terms as mostly interchangeable, but with a small distinction. An executor is the person specifically named in a will to settle the estate. A personal representative is a broader, more modern term that includes executors as well as court-appointed administrators who manage an estate when there is no will. In practice, the duties are the same, and many states now use “personal representative” for both roles.

Practical Next Step: Don’t get bogged down by the terminology. The court documents, called Letters Testamentary (for an executor) or Letters of Administration (for an administrator), will clarify your official title and grant you the legal authority to act.

How can I decline or resign as the named executor?

You are never forced to accept the role. If you haven’t taken any action on behalf of the estate, you can formally decline by filing a document called a “Renunciation” or “Declination” with the probate court. If you have already started your duties and received court appointment, you must petition the court to resign. You will likely need to provide a valid reason and a complete accounting of your actions to date.

Practical Next Step: If you wish to decline, do so immediately before the probate process begins. If you need to resign, consult a probate attorney to ensure you follow the correct legal procedure and are properly discharged of your duties.

How do executors get paid?

Executor compensation is governed by the will or state law. Some wills specify a flat fee or waive payment entirely. If the will is silent, state laws provide a formula, often a percentage of the estate’s value (typically 2-5%). This fee is considered taxable income and must be reported on your personal tax return.

Practical Next Step: Keep a detailed log of your time and all expenses you pay out-of-pocket. Whether you take a fee or not, you are entitled to be reimbursed for legitimate estate expenses. Discuss the fee structure with an estate attorney to ensure it’s calculated correctly according to local rules.

What happens if there is no will?

When someone dies without a will, they have died “intestate.” State law, not the family’s wishes, dictates how assets are distributed. These laws, known as intestacy statutes, create a strict hierarchy of heirs, usually starting with the surviving spouse and children. The court will appoint an “administrator” to manage the estate, and this person has the same duties as an executor.

Practical Next Step: A close relative must petition the probate court to be appointed administrator. Due to the legal complexities of intestacy, it is highly recommended to hire a probate attorney to guide you through this process.

Do Powers of Attorney or Advance Directives work after death?

No. A Power of Attorney (POA), whether for financial or healthcare matters, automatically terminates at the moment of death. The agent’s authority ends completely. Similarly, an advance directive (like a living will) guides medical decisions during life and has no legal power after death. The executor, once appointed by the court, is the only person with authority over the deceased’s assets.

Practical Next Step: If you were the POA agent, your final duty is to provide all records to the named executor. Do not use the POA to access accounts or manage property after the person has passed away.

How is a guardian or conservator different from an executor?

These roles operate at different times. A guardian or conservator is appointed by a court to manage the personal and/or financial affairs of a living person who has become incapacitated. Their authority ends immediately upon that person’s death. An executor’s authority begins only after death, once appointed by the probate court to settle the deceased’s estate.

Practical Next Step: A guardian must file a final report or accounting with the court that appointed them, detailing all actions up to the date of death. They then turn over all remaining assets and records to the executor.

How do I find hidden or digital assets?

Start with a thorough search of the deceased’s home for physical documents like bank statements, tax returns, deeds, and life insurance policies. Check their mail for several months. For digital assets, look for password managers or lists. Most states have adopted the Revised Uniform Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act (RUFADAA), which gives you a legal path to request access, but it can be a slow process.

Practical Next Step: Use free online resources like the National Association of Unclaimed Property Administrators’ website. For digital accounts, consult an attorney if a company is uncooperative, as the legal landscape is still evolving.

How should I handle creditor claims and a contested will?

For creditors, you must follow a formal notification process required by your state, which often includes publishing a notice in a local newspaper. You have the right to dispute any claim you believe is invalid. If a will is contested, all distributions stop. The challenge moves through the court system, which can be a lengthy and expensive process of litigation.

Practical Next Step: Never ignore a creditor claim or a notice of a will contest. These situations require immediate legal advice. Hire an experienced probate litigation attorney to represent the estate’s interests.

How long does probate usually take?

While every estate is different, a straightforward probate process typically takes between 9 and 18 months. The average settlement time in the U.S. is about 16 months. Factors that can significantly extend this timeline include will contests, complex assets like a family business, creditor disputes, or the need to file a federal estate tax return.

Practical Next Step: Communicate this realistic timeline to beneficiaries early and often to manage expectations. You can find state-specific timeline estimates on local probate court websites or by consulting an attorney.

Do beneficiary designations override a will?

Yes, absolutely. Beneficiary designations on assets like life insurance policies, retirement accounts (401(k)s, IRAs), and payable-on-death (POD) bank accounts pass directly to the named person outside of probate. The instructions in the will have no effect on these assets.

Practical Next Step: As executor, you should help beneficiaries by providing them with a death certificate and contact information for the financial institution, but the transfer is between them and the company. These assets are generally not under your direct control.

What taxes apply and how long must I keep records?

Several tax returns may be required.

- A final personal income tax return (IRS Form 1040) for the year of death.

- An estate income tax return (IRS Form 1041) if the estate generates more than $600 in gross income.

- A federal estate tax return (IRS Form 706) only if the estate’s value exceeds the federal exemption ($13.61 million for 2024).

- A state estate or inheritance tax return, depending on where the decedent lived and the value of the estate.

Practical Next Step: Keep meticulous records of every single transaction. It is a best practice to retain all estate records, including tax filings and the final accounting, for at least seven years after the estate is formally closed. For tax guidance, refer to IRS Publication 559, Survivors, Executors, and Administrators, and strongly consider hiring a CPA.

How do long-term care contracts affect the estate?

Any outstanding balance owed to a nursing home or care facility is a debt of the estate that must be paid. Some contracts include binding arbitration clauses, which can limit your ability to sue the facility in court over issues like neglect. Furthermore, if the decedent received Medicaid benefits, the state will likely file a claim against the estate through the Medicaid Estate Recovery Program to recoup costs.

Practical Next Step: Locate and carefully review the long-term care admission agreement. If you see an arbitration clause or receive a claim from Medicaid, consult with an elder law or estate attorney immediately to understand the estate’s rights and obligations.

Final Takeaways: Practical Next Steps and Resources

Navigating the role of an executor can feel like being handed a map to a country you’ve never visited, right after a deeply personal loss. But this journey, while complex, is manageable. Think of it not as one overwhelming task, but as a series of distinct phases, each with its own priorities. As a family caregiver, you already possess the patience and organizational skills needed to succeed. This final chapter pulls everything together into a practical action plan, connecting your past caregiving duties to your future executor responsibilities and equipping you with the resources to move forward confidently.

The process of settling an estate unfolds over a clear, albeit sometimes lengthy, timeline. Let’s recap the major milestones.

- Immediate Tasks (The First Two Weeks)

This is the triage phase. Your first priorities are to secure the deceased’s tangible property, including their home, vehicles, and any pets. Obtain at least 10 to 15 certified copies of the death certificate; you will need them for nearly every administrative task. Locate the original will and other crucial documents like trusts, deeds, and insurance policies. Notify family, friends, employers, and relevant government agencies like the Social Security Administration and Veterans Affairs. - Initial Administration (1–3 Months)

With the immediate needs met, you’ll move into the formal legal process. This involves filing the will with the local probate court to be officially appointed as executor. The court will issue Letters Testamentary, the legal document proving your authority. You must then formally notify all beneficiaries and known creditors of the death. During this time, you will also apply for an Employer Identification Number (EIN) for the estate and open a dedicated bank account to manage its finances. - Probate and Asset Management (3–12 Months)

This is the longest and most labor-intensive phase. You will conduct a thorough inventory of all estate assets, from bank accounts and real estate to personal belongings, and get them professionally appraised if necessary. You’ll manage the estate’s finances, pay ongoing bills, and handle claims from creditors. This period is also critical for taxes. You must file the deceased’s final personal income tax return (Form 1040) and the estate’s income tax return (Form 1041) if it generates income. If the estate is large enough to be subject to federal estate tax, you’ll file Form 706. - Long-Term Closure (12+ Months)

Once all debts are paid and tax obligations are cleared, you can prepare a final accounting for the court and beneficiaries. This document details every transaction that occurred during the settlement process. After the accounting is approved, you will distribute the remaining assets to the beneficiaries according to the will. Your final step is to petition the court to formally close the estate and discharge you from your duties as executor. The entire process takes, on average, 16 months.

Your experience as a caregiver provides a unique advantage. The legal documents you managed before death directly inform your actions as an executor. The Power of Attorney you held may have ended at death, but the financial literacy you gained is invaluable for inventorying assets. Advance directives, while no longer legally binding, offer insight into the decedent’s values, which can be helpful if discretionary decisions arise. And those long-term care contracts you reviewed are now critical for identifying potential creditors and understanding any outstanding financial obligations the estate must settle.

To navigate this path, you’ll need reliable resources. Here’s where to look.

- Local Probate Court Rules

Every jurisdiction has its own deadlines and procedures. The best source is the official website for the probate or surrogate’s court in the county where the deceased lived. Search online for “[County Name] Probate Court” or “[State Name] Judiciary.” - State Bar Referral Services

If you need legal help, your state’s Bar Association offers referral services that can connect you with qualified probate attorneys in your area. This ensures you find a professional in good standing. - IRS Publications and Forms

The IRS is your primary resource for tax matters. Key documents include Publication 559, Survivors, Executors, and Administrators, which is an essential guide. You will also work with Form 1041 (U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts) and, for large estates, Form 706 (United States Estate Tax Return). - Selecting Professional Help

When choosing a probate attorney or CPA, look for someone who specializes in estate administration, has experience with estates of a similar size and complexity, and offers a clear, transparent fee structure. Ask for references and trust your instincts. - Document Retention

As a general rule, keep all estate-related records, including tax filings, receipts, and court documents, for at least seven years after the estate is formally closed. This protects you in case of future audits or disputes.

As you move forward, hold onto these four principles. Always verify state-specific deadlines, as missing one can create significant delays. Maintain meticulous, organized records of every transaction, communication, and decision. Communicate proactively and transparently with beneficiaries to manage expectations and build trust. Finally, never hesitate to seek professional help for complex tax questions, potential legal disputes, or any area where you feel uncertain. You are not expected to be an expert in everything.

Here is a checklist of your immediate next steps.

- Obtain 10-15 certified copies of the death certificate.

- Locate the original will and other essential legal documents.

- Secure all physical assets, including the home, vehicles, and valuables.

- Notify key parties, including the Social Security Administration and financial institutions.

- Schedule a consultation with a probate attorney to understand your state’s requirements.

- Begin a detailed list of all known assets and debts.

- Set up a dedicated filing system to keep all estate paperwork organized from day one.

References

- Estate Administration Timelines: What to Expect — Depending on how complicated the estate is and any potential disagreements, closing the estate can take anywhere from 9 to 24 months or even …

- Executor of a Will Duties and Responsibilities: A Step-by-Step Guide — Estate closing (12–24 months): File final accounting, obtain court approval for distributions and executor discharge, and complete final …

- Executor's Checklist for Probate Responsibilities and Timelines — 1. Locate the Will and File for Probate · 2. Notify Interested Parties · 3. Inventory the Estate · 4. Pay Debts and Taxes · 5. Distribute Assets to …

- Your Ultimate 2025 Settling An Estate Checklist: 8 Key Steps — This guide will break down the entire process into eight manageable stages, empowering you to manage your duties effectively. From locating …

- Estate Settlement Timeline: When Will I Get My Inheritance? — In California, an executor typically has one year from the date of appointment to settle an estate. However, this deadline is extended to 18 …

- How Long Does an Executor's Job Typically Take? — Settling an estate takes an average of 16 months, according the software company EstateExec, and the settlement process requires an average of roughly 570 hours …

- Estate Settlement Process Explained: U.S Checklist – ClearEstate — The estate settlement process can take between 12 – 18 months, maybe more and beneficiaries should be aware of this timeline. Every estate is …

- General Timeline for Probate – Alatsas Law Firm — Prepare and File the Probate Petition (1-4 months) · Provide Notice to Creditors (3-6 months) · Payment of Debts and Fees (6-12 months) · Asset Inventory (6-12 …

- Executor's Checklist: What are the 7 Key Duties During the Probate … — 1. Locate the Will and Initiate the Probate Process · 2. Notify Beneficiaries and Relevant Parties · 3. Inventory and Secure the Estate's Assets.